I stagger onto the town dock in Bucksport, Maine, at 4:24 a.m., hungry for a hot breakfast and redemption from the day before’s debacles with #41 and Muse. The Penobscot River lies flat as newspaper in the predawn dimness. Though windless and well above freezing, the drizzly morning air makes me shiver inside my hooded jacket. I light a cigar to ward away the chill at the risk of contracting throat cancer.

Bucksport’s the northernmost stop on my cross country itinerary, and it attests to the gaping expanse of America’s geography, what Jack Kerouac called “the groaning continent.” I’m now about 120 miles closer to Quebec City, Canada, than Sag Harbor, New York. And yet, I’m still more than 238 miles, or nearly five hours drive, south of Madawaska, Maine, the border crossing near the top tip of the state.

A few hundred yards upriver, smoke billows from the stack of the Champion International mill. The mill provides paper for Newsweek, Sports Illustrated, and Reader’s Digest, three of the glossy magazines that once provided me with employment or freelance assignments. The demise of print journalism doesn’t exactly bode well for people hoping to make a buck in Bucksport.

On the stroke of 4:30 a.m., Greg Perkins sidles up to the dock in a twenty-one foot lobster boat named Jenny. He’s decked out in a gray hoodie and orange overalls that match his ruddy cheeks. A lean, lanky 19 year old, Greg is one of Maine’s youngest lobster boat captains. I’d contacted him via a lobstering web site a few weeks earlier, and he’d agreed to show me the ropes, traps, and buoys of his trade.

“Mornin’,” he hollers, waving at me.

“More like midnight,” I mutter, waving back.

I flick away my cigar, and pull a collapsible camera tripod out of my jacket. Composed of plastic and aluminum and sold at Radio Shacks everywhere for $15.99, the tripod promises to be one of my most valuable pieces of equipment. It weighs less than two pounds, but it stands 50 inches tall when fully extended, enabling me to video myself without assistance when I need to do what TV producers call a “stand up.”

I attach my Flip camera to the threaded screw at the top of the tripod, and shoot a test segment while Greg ties up the Jenny.

“Why the hell do we have to go out so early?” I ask.

“One of the reasons is the weather,” Greg says. “You want to haul your gear before it gets windy, and the wind usually doesn’t blow too hard this time of morning. Fishing up here in the mouth of the river we have a real strong current. But right now we have an incoming tide that kind of counteracts the current so we can get to the gear before the buoys get pulled under water.”

“Yeah, okay,” I grumble. “You’re the captain.”

###

Despite the foul weather and my fouler mood, I’m still looking forward to our expedition. Lobstering is a classic American small business, with an estimated 6,200 sole proprietors who own and operate their own boats in the state of Maine alone. Maine lobsters are an iconic brand. They compete with imports from Canada, but they can’t be outsourced to India or China.

Unfortunately, Maine lobstermen are proving to be almost too good for their own good. Thanks to decades of conservation practices, they’ve inadvertently created a glut. Wholesale prices have plunged from $10 a pound in 2007 to only $3.50 a pound. “Not too long ago, a lot of guys made six digits a year lobstering, easy,” Greg tells me. “No one’s doing that now. If you’re covering expenses, you’re doing good.”

Greg’s a sophomore at the University of Maine in Bangor, about twenty miles up the road, majoring in business management. I ask what could possibly possess a college-educated guy to go into lobstering instead of banking or stock trading.

“I’ve been coming out on Penobscot Bay since I was 11, 12 years old, and I’ve always loved fishing,” he says, grinning sheepishly. “I just figured why not try to make a job out of it. I’ve got a small boat, and I don’t have that much expenses; I don’t have any boat payments. I definitely want to do it in the future, but prices are really bad right are now, and I just don’t know if I can make a living at it.”

I can’t offer Greg much more than a sympathetic ear and a copy of the Flip video I shoot. His state-issued student license does not allow him to train a novice like me or even let me handle his gear. That’s probably just as well. The next day, I’m scheduled to go out on a tour boat downstate, where I’ll be able to try my luck at hauling traps. In the meantime, I have a rare opportunity to observe a real lobsterman at work.

Greg lays one of his traps on the dock to show me the main parts. It’s a four foot long rectangular box made of yellow steel mesh, and it weighs about forty pounds including the handful of bricks used to sink it. The far right section of the box, known as the “kitchen head,” has an opening to accommodate incoming lobsters and crabs, and a wire for stringing the bait of choice, which is fresh herring. A metal ramp connects the kitchen to the left section of the trap, known as the “parlor.”

“Lobsters and crabs will crawl into the trap and fall down into the kitchen,” Greg informs me. “They can’t get out because they can’t climb back up through the entry hole very easily. Then they see the ramp going into the parlor, and they start crawling in that direction. It looks like a way out, but it really just takes them further into the trap.”

“So you‘re actually tricking the little critters?” I ask.

“Eh-yup,” he replies in the peculiarly accented diphthong people in Maine utter when they mean yes.

The Maine Department of Marine Resources limits the number of traps an individual lobsterman can put in the water to 800. Greg’s put in 100 traps, marking their exact locations with a GPS device. “If you poach on another lobsterman’s area, they'll just cut your buoy rope and your trap will sink to the bottom of the bay,” he says.

The whole scenario seems like an almost too perfect metaphor for male-female relationships. Enticed into the kitchen with a savory meal. Lured into a parlor that appears to offer a convenient way out if needed, only to realize you’ve gone even further into the trap. Cut off at the end of your rope, and left to drown.

“You have a girlfriend?” I ask Greg when we shove off from the town dock.

“Nope. Not at the moment.”

“Might want to keep it that way for awhile.”

“Eh-yup.”

###

The sky and water remain ghostly gray as we pass under the newly completed Penobscot Narrows Bridge. Intermittent raindrops pelt the windshield. I notice that there are no other boats out on the water, and nary a sound save for the growl of the Jenny’s outboard motor, which generates 70 horsepower, the same as my Smart Car.

We come upon Greg’s first trap not far from the mouth of the river. It’s strung from a buoy painted with his chosen colors, white with a single red stripe around the top. Greg cuts the engine, and slips on a pair of blue rubber gloves. He snares the buoy rope with the iron hook of a gaff, slings the rope around the spool of a metal device called a hauler, and turns on a converted lawn mower motor below deck.

The boat shakes like a giant vibrator until a yellow metal trap bursts up through the surface of the water. I count two lobsters and nine Jonah crabs huddling beneath thick clumps of leaves and gobs of river bottom mud.

Greg opens the top door of the trap, and grabs the lobsters by their tails so as to avoid being pinched by the claws. He places a flat metal gauge between each lobster’s eye sockets and carapace. According to federal conservation regulations, a lobster has to be released if it measures less than 3 1/4 inches, which means it’s baby, or more than 5 inches, which means it can only spawn with other big lobsters.

“These are keepers right there,” Greg says. “Measure four inches long. Probably weigh a little over a pound and a quarter.”

He secures rubber bands around the lobsters’ claws with the help of a pliers-lie tool, and drops them in a tub filled with salt water. Then he snatches up the few handfuls of partially gnawed herring that remain in the trap, and flings them overboard. Immediately, a flock of seagulls descends, gobbling up the herring amid a thrashing of beaks and wings reminiscent of Muse’s gesticulations in recent discussions about my road trip.

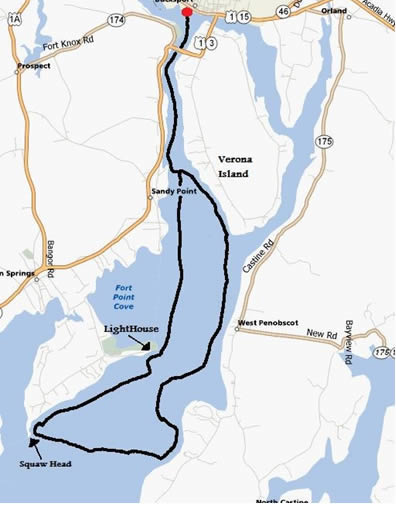

Over the next five and a half hours, we pass the tree lined shores of Verona Island, the antique lighthouse near Fort Point Cove, and mysterious looking islands in the vicinity of Squaw Head. Greg retrieves about 250 pounds of Jonah crabs but only four more lobsters. He says it isn’t worth the trouble to take less than a dozen lobsters to market, so he steers the Jenny to a secret location near the mouth of the river, where he hauls up a storage trap and stashes the day’s catch with a half dozen previously caught lobsters.

“We don’t get to the peak for lobstering up here until September,” he says on the ride back to Bucksport harbor. “Right now, I could sell the ones I’ve got off the boat for $4.50 a pound. I’m going to keep ‘em in underwater storage until this coming Fourth of July weekend so I can get a little better price.”

When Greg brings the Jenny back to the dock around half past eleven, the sun still hasn’t parted the overcast, and he still has a couple of more hours work ahead of him that includes washing down the boat and driving the crabs to market. I ask him to tally the bottom line as I prepare to shoot a closing stand up.

“Well, my expenses for gas and bait were about $70. I can sell the 250 pounds of crab for about $90. I’ll get about $40 more for the lobsters.”

“So you’re going to net about $60, or less than seven bucks an hour, for close to 9 hours of work?”

“Eh-yup,” he confirms.

###

That afternoon, I depart Bucksport for Rockland, the self-proclaimed lobstering capital of the state. I start feeling sorry for my young captain friend. Then I remind myself that I’ve already spent close to $400 on food and lodging in less than three days. At age 19, Greg Perkins still has a chance to find another profession. I should be so lucky as an unemployed former print journalist pushing sixty.

My personal World of Hurt gets more painful shortly after I check into a motel across the street from the Maine Lighthouse Museum in the center of Rockland. The Flip video footage I shot that morning is a vast improvement over the silhouetted mess I made of #41. But now there’s a problem with my web host’s administrative program.

In theory, I’m supposed to be able to upload still photographs and videos from my MacBook Pro to the appropriate pages on www.harryworldofhurt.com. When I log onto the admin site, however, the boxes and icons for uploading do not appear.

Panicked, I call my web host. I’ve nicknamed him Ozzy because he has the same dissolute face and long scraggly hair as the rock star Ozzy Osbourne. He always talks super fast and curtly, as if he’s preoccupied with more important clients. Not surprisingly, Ozzy refuses to accept blame for the uploading glitch.

“Problem’s your Apple. You need to get it checked.”

“Can’t do that until I pass back through New York City.”

“Whatever,” he says like a dismissive teenager.

Miffed, pissed, and even more panicked, I guzzle half a bottle of red wine as I check my emails. I very nearly delete a message from Muse. Good thing I catch myself. She’s sent me an original Grimm’s Fairy Tale all about us.

“Once upon a time in a noble fishing village by the sea, there lived a tall blond woman and a tall blond man, both with very small noses and slanted blue eyes,” she writes. “He called her his Muse and she called him her Schreiber, and they had sex two slaves who were named Hermann and Hermeinie. They fell very much in love with each other. They kissed and cuddled and giggled and drank and danced and worked and traveled together, and they were so happy in their bubble, they thought nothing could harm them.

“Although already the first year, the encountered Goblins and Ogres and Witches, they simply laughed at them and continued their journey in bliss. The second year, the weather got colder and the food scarcer, but they felt like they were invincible because she thought he was brilliant and handsome and he thought she was inspiring and beautiful. Sometimes there were a few harsh words between them, but their sex slaves Hermann and Hermeinie usually patched things up quickly.

“However, in the third year, the winds began really to howl. The Ogres, Witches, and Goblins emerged in droves. Muse and Schreiber just forged on, even after a nasty battle with a Paper Dragon that almost severed Scheiber’s writing hand. But the nasty words between them came more often. At first Muse thought nothing of this, but then she became increasingly scared and insecure and finally, angry. Her own work (she had art to herself) started to suffer. She felt she was drowning in all of his battles.

“Soon there was not much of the laughter or the dancing. Muse and Scheiber stopped exchanging their ideas and visions and plans. They ventured more and more apart. Muse thought Schreiber did not love her anymore. He told her he did, but it felt untrue because of all his raging and screaming. He thought she was a melodramatic bore who was never happy anymore. She stopped laughing at his jokes, and became angrier, and stopped trusting, and finally, she looked ugly. They drank more and played less, and their sex slaves Hermann and Hermeine were ready to throw in the dish towel.

“Soon they began to sit in their own towers alone, drawing up the bridges. The brave Schreiber thinks he can fix them, but actually he is embarking on a journey all on his own and his own doing with only a turtle as a companion to fight Demons. Muse stays behind because there is no place or function in this adventure for her, which makes the Muse both sad and relieved, as she has no intention to wait around for him to return with slain Dragons or to wait until he asks her to join him.

“Instead, Muse will finally be able to go back to her old Other Country, and tend to her long neglected work and family. And so they will live happily ever after, but not together...unless... it’s THE END... or TO BE CONTINUED...”

My panic and anger give way to aqua-eyed remorse, the tears of a clown when there’s no one around. I take care to save the email, twice. Then I call Muse on my iPhone.

“Your fairy tale is fantastic and loving and true,” I say. “But it needs a happier ending.”

“Then why do you hang up on me last night?”

“Listen, I’m sorry. I was just upset because I screwed up the Bush video.”

“But you get mad at me.”

“I wasn’t mad at you. I was mad at me. I love you. Du bist meine Muse.”

There’s silence on her end. After the passage of many seconds, I tell her that the kid boat captain I went out with that morning nabbed a few lobsters.

“You are bringing some of Captain Kid ‘s lobsters home for me?”

“No. I don’t have any. He put them in underwater storage.”

“You don’t give me lobsters,” Muse returns, “I don’t give you nooky.”

Then she hangs up on me.

Photograph Captions and Credits: 1. Greg Perkins with fresh caught lobster, Penobscot Bay, ME 2. Lobster trap (HH3) 3. Map of fishing area (Greg Perkins) 4. Jonas crabs (HH3)